5 hours ago

Why The Cowardly Lion Still Roars: Queerness at the Heart of Oz

READ TIME: 4 MIN.

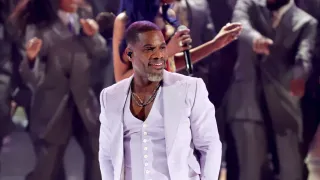

Let’s be honest: to walk the yellow brick road is, in many ways, to journey through queer history itself. For generations, LGBTQ+ people have claimed The Wizard of Oz as a cultural touchstone, but no character in Oz radiates queerness quite like the Cowardly Lion. He’s not just a beloved “friend of Dorothy”—he’s been camp, coded, and quietly radical since his first roar. And in 2025, as Colman Domingo steps into the Lion’s paws in the much-anticipated Wicked film, it’s the perfect moment to ask: Why do queer folks see ourselves in this mane-tossing, melodramatic, nervy icon?

From his first appearance in the 1939 MGM classic, the Cowardly Lion is more than a comic foil. Bert Lahr’s performance turned the Lion’s “cowardice” into something distinctly queer—an over-the-top display of camp, effeminacy, and coded language that LGBTQ+ viewers instantly recognized, even if mainstream audiences didn’t have the vocabulary yet. There’s the famous limp wrist gesture, the sibilant “esses” as he calls himself a “sissy” and a “dandelion,” and that immortal line: “Yeah, it’s sad, believe me, Missy / When you’re born to be a sissy / Without the vim and verve.”

Film scholar Alexander Doty embraced this camp spectacle, writing, “King of the forest? He was more like a drag queen who didn’t give a fuck. Because of this, he seemed to have a bravery that the narrative insisted he lacked.” The Lion’s “failure” of masculinity—his softness, his retreating nature, his flair—reads as queer not just in mannerism, but in the narrative itself. As Dr. Hollis Griffin, a media scholar, puts it: “His softness, his retreating nature, his wimpiness, for lack of a better way of saying it, gets coded on gendered terms as a failure of masculinity. There’s a way that a failure of masculinity reads queerly.”

For decades, critics and audiences debated whether the Lion’s queerness was meant as a joke or a jab. It’s true: the “sissy” character was often played for laughs, and some viewers see self-hatred in the Lion’s longing for courage. But generations of queer people have read the character against the grain, finding power in his vulnerability and seeing his journey as an allegory for coming out and self-acceptance.

The Lion’s confession—“I thought I’d be safe here, no one would discover my terrible secret. That I’m a lion without any courage!”—echoes the fraught coming out experiences of many LGBTQ+ people, especially in times and places where difference meant danger. In the 1970s, as gay liberation took center stage, this “confession” became a symbol of pride, a moment of naming one’s truth in a world that demanded conformity.

As the Lion’s journey unfolds, he learns—alongside Dorothy, the Tin Man, and the Scarecrow—that what he seeks is already inside him. It’s a message that resonates deeply with queer audiences: you don’t need to change who you are to be worthy of love, home, or community.

The Cowardly Lion is pure camp in the most glorious sense: self-aware, excessive, theatrical, and deliciously subversive. His big mane, painted face, and fondness for bows and showtunes? Drag before the term was mainstream. When the Lion sings, struts, or flops dramatically to the ground, he’s not just hamming it up—he’s performing resistance, playfully poking holes in the idea that masculinity (or any gender) is a fixed ideal.

As writers Dee Michel and James Satter put it, “Lahr’s performance is so hammy, so over the top, that he draws attention in every scene he’s in. In addition, his campiness and flamboyance demonstrate how silly masculinity is; it is something created by society, not an innate quality.”

The evolution of the Cowardly Lion’s queerness doesn’t stop at 1939. In The Wiz, the Lion’s soulful vulnerability, performed by Black artists, weaves Black queer subculture into the heart of Oz, expanding the Lion’s resonance and representation. The forthcoming Wicked adaptation, with Colman Domingo—an out, Black, gay actor—taking center stage, signals a new era for the character. This casting places Black LGBTQ+ identity squarely at the story’s center, inviting new generations to see themselves reflected in Oz’s magic.

The Wizard of Oz isn’t just a spectacle; it’s a parable of chosen family and self-realization—core themes in queer life. Dorothy’s acceptance of her oddball friends, her journey beyond the drab world of Kansas into the dazzling, technicolor freedom of Oz, and her famous alliance with the “friends of Dorothy” all echo the queer experience of finding belonging outside the mainstream. Scholars have even pointed out that the phrase “friend of Dorothy” became code for queer identity itself, and the Lion’s distinctive persona was no small part of that history.

Today, as anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric rises and the fight for authentic representation continues, the Cowardly Lion’s journey remains a powerful reminder: vulnerability and difference aren’t weaknesses—they’re the source of our greatest courage. Whether you see him as a camp icon, a drag queen in disguise, or simply a lovable oddball, the Lion’s legacy endures because it invites us all to come out, claim our space, and roar with pride—even if our voice shakes.

And that’s the real magic of Oz: it’s always been a little bit queer, and the Cowardly Lion has always been at its fabulous, fluttering heart.